"Aren't You A Little Short For A Stormtrooper?" — UC Berkeley's Vice Chancellor Mogulof Mans The Velvet Rope At Presumed "D-Day" For People's Park

What Does It Mean When You Have To Call Up 1,400 Police to Suppress Fewer Than 50 Rag-Tag Protesters at People's Park? And What Were The Restrictions on Reporters?

It was nearly one a.m. on Thursday when a young Asian-American woman approached me at the police blockade on Channing Street in Berkeley, a block away from People's Park. As many as 1,400 police officers had been summoned by the University of California to quash any resistance, peaceful or otherwise, during what the University hoped would be the "final" closing of the park, which had begun an hour before, just before midnight on Wednesday. Even adjacent streets not immediately bordering the park (such as Channing) had been blockaded by CHP officers in riot gear.

"Would you go with me to ask the officers for their badge numbers?" the young woman asked me in a quiet voice. At this particular blockade, a young man had been detained after asking to cross. He had said he lived there, and just as suddenly it seemed he was handcuffed by police and placed on the curb about 25 meters ahead of us.

I agreed to accompany her, and we walked toward the officers. By temperament and style, she did not seem to be connected to the detainee. What had brought her out on this cold night? Was she a law student? Several of the arresting officers provided her their information, but other officers refused to comply, and this non-compliance was smilingly permitted by their supervising officer.

Then, behind me, an argument about access to the restricted area ensued between a male reporter and a CHP officer, and subsequently between the same reporter and a Berkeley police officer. When the BPD officer said that press could get access on Bowditch, I followed over to Bowditch with the other reporters.

And there in the darkened street, surrounded by the din of the bulldozers and the trucks still delivering barriers, stood a man much-hated by the activist class in Berkeley: Dan Mogulof, Assistant Vice Chancellor for Executive Communications for UC Berkeley. Mogulof the Mighty! Destroyer of Parks!

Meet Dan Mogulof

Mogulof, for all his fearsomeness and high status within the University system, looks a bit like Larry David, but he was dressed like any number of New York asset managers on a winter weekend in Setauket: a slim jacket, an expensive scarf curled inside his collar, and khakis. He carried with him a slight air of authority that belied his true power on the scene: That night, reporters could only gain access if Mogulof, the ultimate arbiter of the evening's velvet rope, decided to let you in.

One of the TV news reporters had a back-and-forth with Mogulof about access and First Amendment rights. Then Mogulof looked at me, and said, "And you are...?" I told him my name, identified a prominent New York publication which had previously published my work, and then, somewhat tremulously, pointed out that no one should be restricted from the site. Mogulof looked at me archly and asked "Okay, but are you here as a journalist?" I sighed and told him I was here as a reporter. And thus, at the wave of Mogulof's hand, the metal gate was lifted and parted by a police officer dressed like a storm trooper and armed to the teeth (how much was that costing us?) and we were let through — but only because Mogulof personally approved.

That was the enforcement en scène: arbitrary, and in violation of basic civil rights not only for reporters, but for any member of the public. Still, if you restrict something, and then you allow it, you might think that reporters would be satisfied. But one of the reporters with the TV news crew had been in a particularly aggravated state over the lack of access and, as we were escorted into the blockaded area, he engaged in a back-and-forth with Mogulof, challenging him on the legality of the restrictions. I was grateful that the reporter was pushing back, not just because pushing back against overarching authority is the right (if difficult) thing to do, but because Mogulof's explanation was worth getting on camera.

The Gates Are Opened, Kind Of:

As the gates were parted, Mogulof made clear to the officers that no one was to enter without permission from him or a member of his staff, whom he did not name. (One CHP officer in riot gear appeared to salute – I couldn't tell if that was compulsory given the chain of command implied by the "emergency order" or if it was offered in jest.)

As he escorted us, Mogulof explained that: "So there's still a number of people in the park, I'm just going to ask you guys to stay on the corner for right now. Uh, right up here, you'll be able see into the park, nothing's really started yet. There have been a few arrests, I don't know how many people have been given a dispersal order.”

The aggravated reporter then asked: "Can you explain to me what kind of permit you were given to close this down?"

Mogulof responded: "We don't need a permit. We own the land."

Reporter: "This is public property."

Mogulof: "No, it's University property."

Reporter: "The sidewalk?"

Mogulof: "Oh, it's with the City. We, yeah, we took a permit from the City."

Some of the reporter's subsequent question was lost in the audio recording, but it questioned the specifics of the permit.

Mogulof's answer is fortunately preserved on the recording; he replied: "Under California law, this is a crime scene, there's police activity here, and we have the ability to hold people back."

Reporter: "Not for lawful assembly."

Mogulof: "Uh, no. Actually, when it's a first amendment issue, that's overridden... when there's a police operation, when there's a crime scene–"

Reporter: "Only when there's (inaudible) involved." (I believe the word he used is construction, but that part is too muffled to be certain.)

Mogulof didn't respond to that comment directly. Instead, he said: "So, I'm going to ask you to stay on the (inaudible), you do what you want, I'm not going to force you, I'm not going to run you down and tackle you, but you know what the law is, and obviously we have (inaudible) so it's up to you how you want to deal with it."

(It went over my head at the time, but I would generally not have envisioned a Vice Chancellor at the University of California suggesting even the possibility that he might tackle anyone.)

Reporter (sharply): "I have attorneys who know all about this."

Mogulof: "You know what? You want to start out the evening with an attitude?"

You want to start out the evening with an attitude? It was as if Mogulof had embarked on a particularly ill-matched dinner date.

Reporter: "No, I'm just telling you–"

Mogulof: "All right, but you're wrong about the law, and, it's up to you."

With this comment, Mogulof reminded the reporter that it was Mogulof, and not the reporter, who had the power here. Could the reporter have been disinvited at that point? As Mogulof had made clear, no one came through the barrier without the permission of himself or a member of his staff.

The Park:

At that point Mogulof had escorted us to the intersection of Haste and Bowditch, at the Northeast corner of historic People's Park. Berkeley has never suffered from too much streetlight, but tonight, the park was blindingly bright, courtesy of multiple floodlights, and it continued to fill with police in riot gear. A female reporter asked him what was going on at the scene, and Mogulof mentioned that there were propane tanks that they were worried about.

Mention by Mogulof of propane tank concerns at 1:22 a.m. is noteworthy. I later learned from one of the activists that, at approximately 12:02 a.m., University of California riot police had started chainsawing their way through the wall of the People's Park kitchen, despite having been informed that there was a propane tank on that side. UCPD officers were informed of this fact by the three people who were still inside the kitchen when UCPD started to chainsaw into the kitchen. For all that, UCPD did not manage to gain access to the kitchen until 12:46 a.m., despite having attempted to chainsaw through the kitchen's roof. As one of the activists sighed, "These are the most incompetent police ever."

Mogulof instructed us that "this area right here" would be the spot where we should remain. He insisted that we could "see pretty much everything" from this narrow corner. This didn't quite make sense, since the area of the park extends a full block to Dwight, and approximately 2/3 of a block to Telegraph Avenue.

It was disorienting. I wanted to confirm the number of police within the park, but because of the police line, it turned out to be tricky if not impossible to move throughout the park without risking arrest.

The Activists:

At the moment we arrived, Andrea Prichett of Berkeley Copwatch, long active in the fight for People's Park, used a loudspeaker to alert the crowd to the presence of Dan Mogulof:

"Is that Dan Mogulof? Wow! We got a real UC administrator! Dan Mogulof! We must really rate. Dan's pretty famous."

The protesters, dispersed throughout the park, some of whom were about to be arrested simply for standing in the park, reacted gleefully, and you heard a chorus of voices rising:

"Dan Mogulof!"

"Hey, Danny Boy! Why don't you come over here?"

"Fuck you, Dan! You're kicking us out of our park!"

In reference to UC the Berkeley Chancellor, one of the protesters asked, "Where's Carol Christ?"

And, in a nod to Mogulof's prior service in the IDF, a protester yelled: "Tell us how the Israeli Defense Force was for you!"

There was limited press on hand, and to my knowledge, the TV news crew I had walked in with was the only TV news crew there, prompting a taunt to Mogulof (who had already retreated) from a younger female protester: "I don't see any cameras here! You're here without cameras? What the hell, Dan? That's amazing."

I was still getting my bearings amid the bright lights and the overwhelming presence of police when I saw Russell Bates, a Vietnam veteran and longtime Berkeley Copwatch member who has also long been active at Peoples' Park. He had just seen Dan Mogulof and was uncharacteristically angry. I have only known Bates from City Council meetings, where I always found him to be genial. "I hate that Dan Mogulof," Bates told me bitterly, "for many reasons." Days later, I tried to ask Bates about Mogulof, and was told he was still too upset to talk about it.

For the people who had long provided assistance to the unhoused population that relied on the park for shelter and community, it had been a slow and anxiety-inducing burn. To go to People's Park at any time was to realize how much labor volunteers put into the site, whether it was Food Not Bombs providing 5 meals a week every week for the last 34 years, or Lisa Teague camping in the park to monitor safety, or original 1969 People's Park founder Mike Delacour still fighting for the park in the last year of his life. (One young person from Marin had been volunteering at People's Park for several years, and was generous in sharing with me the timeline they had recorded.)

The closure of the park that had been threatened for approximately 50 years was finally happening, despite an existing lawsuit not having been decided by California's State Supreme Court, and the fact that the developer for the housing the University planned had long ago backed out. This situation actually mirrors the original founding of the park, wherein the area was shut down but never developed, prompting Mike Delacour to propose a concert venue in 1969.

The University's haste to evict on Wednesday night even before the court case had been decided seemed questionably legal to many, but if you can summon 1,400 police officers to your cause, legality may simply be an afterthought.

The Wrecking Crew:

Even though the kitchen had been breached sometime before I arrived, the police and contractors took an enormous time to demolish it, and the din of chainsaws, trucks, bulldozers, and sledgehammers was disorienting.

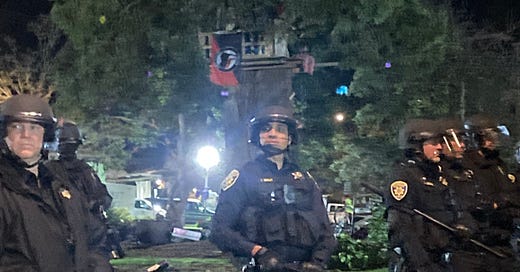

I probably should have been more impressed by the risk implied by the assault on the people in the kitchen, but in the chaos of multiple riot-geared law enforcement agencies encircling the area (Alameda County Sheriff, University of California Police, Berkeley Police Department, and CHP, not to mention Apex security staff) I was distracted by the contractors with chainsaws who were climbing the perfectly healthy shade trees that lined the park along Bowditch. Three protesters remained in the treehouse nestled into the tallest remaining tree, a mighty conifer that stood on the grassy eastern edge of the park. Apparently, the first thing the police had done was to remove the ladder from the treehouse, trapping the protesters in the tree. That conifer was circled, ominously, by University of California Police in riot gear.

I fell into conversation with a street medic, a tall young Asian American man, and it struck me, while watching the police with him, how many younger Asian Americans and Latinos had been involved in supporting Peoples' Park, while many of the police officers were older Asian Americans and Latinos, themselves – a mirror of the generational split in political directions amongst Jewish Americans with regard to Israel/Palestine. It was hard not to recall two young men from what were then considered "ethnic" families – Mario Savio and Jack Weinberg – who had started Berkeley's Free Speech Movement in 1964, both of whom had been involved with Congress of Racial Equality (CORE).

I bring this up because there is no People's Park without the Free Speech Movement. And it almost seems there would have been no Free Speech Movement without CORE. In Berkeley, Savio constantly invoked the lessons he learned from Black civil rights activists and organizers in the American South, it was a kind of North Star for him. This solidarity is mirrored in the solidarity shown at People’s Park between “elite” Cal students who volunteer at the park, and its unhoused residents.

That exceptional solidarity may explain why the FBI cracked down on Savio so ruthlessly, and, as many People’s Park activists believe, why the University cracked down so hard on them.

Meet Jonah Gottlieb

And then suddenly there was a commotion behind the line of police officers. I crouched down to peer between the sea of officers' legs, behind which a young person appeared to have been pushed to the ground and handcuffed. It was Jonah Gottlieb, an organizer with the student section of the Democratic Socialists of America. This would happen three more times to young activists in the two hours I was inside the park, and each time they dragged the young person across the street into a kind of alley behind a driveway on Haste Street. It was dark behind there, and when we tried to follow in order to get badge numbers and monitor the safety of the arrestees, the police threatened us to "move back!", wielding their sticks. This wasn't so different from what I had already witnessed outside the park on Channing.

I later learned that several of "the kids" had been held in a kind of nouveau paddy wagon, a mobile jail that looks a bit like an armoured truck, with very small cells. Many were later processed not in Berkeley, but in Oakland, ostensibly to make it harder for them to make it back home.

I had limited knowledge of Gottlieb, but he did not strike me as the kind of person you arrest unless you wanted to risk creating the next Jack Weinberg. So perhaps we can thank Vice Chancellor Mogulof for that. The world could use more "next Jack Weinbergs".

Getting Out:

I admit I felt sick watching the trees come down, and nervous from watching the protesters in the treehouse, who seemed all too blasé about the threat the riot police posed. On the ground, the riot police were pushing us south toward Telegraph. It was 2:58 a.m. I asked permission to leave the area (I did not want to be treated as Gottlieb or the other arrestees had been), and walked through the small throng of protesters at the blocked entrance to the park.

Outside the blockade, I had encountered a patrician-looking baby boomer couple walking the streets. They appeared stunned by the blockades and the police presence. By their caution around the police, I wondered if they had once been involved in the original People's Park protests that rocked Berkeley in 1969. The woman turned to me and said with regard to the shipping containers that the University planned to install as a barricade around the park, in an echo of the US wall at the Southern border to Mexico, "Can't they be welded open? So the homeless people they kicked out of the park could at least have temporary shelter in the shipping containers?"

Her comment intrigued me. The University had timed this during winter break, when most students were still off-campus. But the students were coming back, and then what? While UC Berkeley is not the hotbed of radicalism that it was once known for, the tide appears to be shifting back, and the current assault on Gaza is moving more students to the left. When I suggested to one Marin County youth that the Peoples' Park issue might distract from Gaza ceasefire activism, he gave me a confident answer: "No, they're going to reinforce one another." It was the kind of confidence Savio and Weinberg had displayed in 1964.

I made it home in the dark by 4 a.m. and took a hot shower. In the chaos created by the riot police, I didn't even realize how cold I had been all night. When I finally crawled into my warm bed with a cup of tea, I thought about the people who had been displaced from the park. Many of them were older than me, and had debilitating injuries. Where would they go?

Follow-Up:

As dawn broke on Thursday morning, the University started stacking the shipping containers to form the barrier around People's Park. And as I write this, on Sunday afternoon, the streets surrounding the park remain blockaded, and residents are required to provide identification papers to return to their homes. ("Morning in America", indeed.) Police engaged in multiple incidents of violence in the days afterward, and lawsuits are anticipated.

Word on the street is that the CHP contract ended today, and so the remaining police forces will be Berkeley Police Department and University of California Police Department. It is not hard to imagine what could go wrong in a scenario where an understaffed Berkeley Police Department is required to patrol an area made unbelievably more combustible by the mismanagement of the University of California.

As for the University's role in violations of First Amendment rights, I spent several hours talking to activists since Thursday morning, and have more interviews lined up. I was surprised that the First Amendment Coalition, a nonprofit that I felt should have had a presence at People's Park on Wednesday night/Thursday morning, responded to my request for an interview, which is being scheduled for this week. More on that in a follow-up.

The origins of People's Park are not well understood. I hope to relate part of that history in the coming weeks, weaving in the experiences of current People's Park activists who have generously shared their perspectives with me. In the meantime, I recommend Seth Goldberg's stunning history of Berkeley in the 1960s, Subersives: The FBI's War On Student Radicals, and Reagan's Rise To Power, which includes a 40-page chapter on People's Park.

As for the 1,400 cops required to clear out a ragtag group of less than 50 protesters from People's Park? What better vindication of the fierceness and integrity of the protesters could any activist possibly desire? It wasn't what the activists wanted, that would take longer. They were ready.

©️2024 Eva Chrysanthe