Editor’s Note: Coverage of the circus that is Marin County will resume after 50th anniversary of the September 11, 1973 coup against Allende. This article marks two 9/11 anniversaries; the 50th anniversary of the Chilean coup, and the 22nd anniversary of the WTC attacks.

Just shy of three years before the World Trade Center attacks, I sat in a conference room on the 30-something floor of Rockefeller Plaza at a once-a-week morning meeting at Lazard Frères. I took careful notes not because I was diligent, but because I didn't know a damn thing about what I'd been hired to write about, and thus didn't have the luxury of simply listening.

Lazard was without question the most polite office I had ever worked in, and the weekly meetings had always been uneventful, until then. One of our WASP managing directors, a man who had been there for decades before we arrived and would remain there long after we "cyclical" peons had moved on, was in a rage.

He was responding to news that General Augusto Pinochet, the former head of the military dictatorship of Chile, had just been arrested in London for human rights violations. The managing director considered the arrest of Pinochet to be a travesty of justice, and he denounced both the Spanish magistrate responsible for the indictment, and the authorities in London.

We underlings were stunned into silence. We shuffled out of the room dutifully when the meeting ended, but once at our cubicles, we burst into nervous laughter: "What was THAT all about?" None of us had been political science majors, but we knew enough about Pinochet's crimes to know his indictment and arrest was long overdue.

"Pinochet threw people out of airplanes," a young CFA whispered, wincing at the thought of it, though that was less violent than some of the other murders committed by Pinochet's crew.

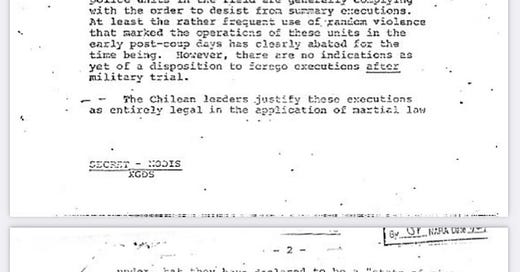

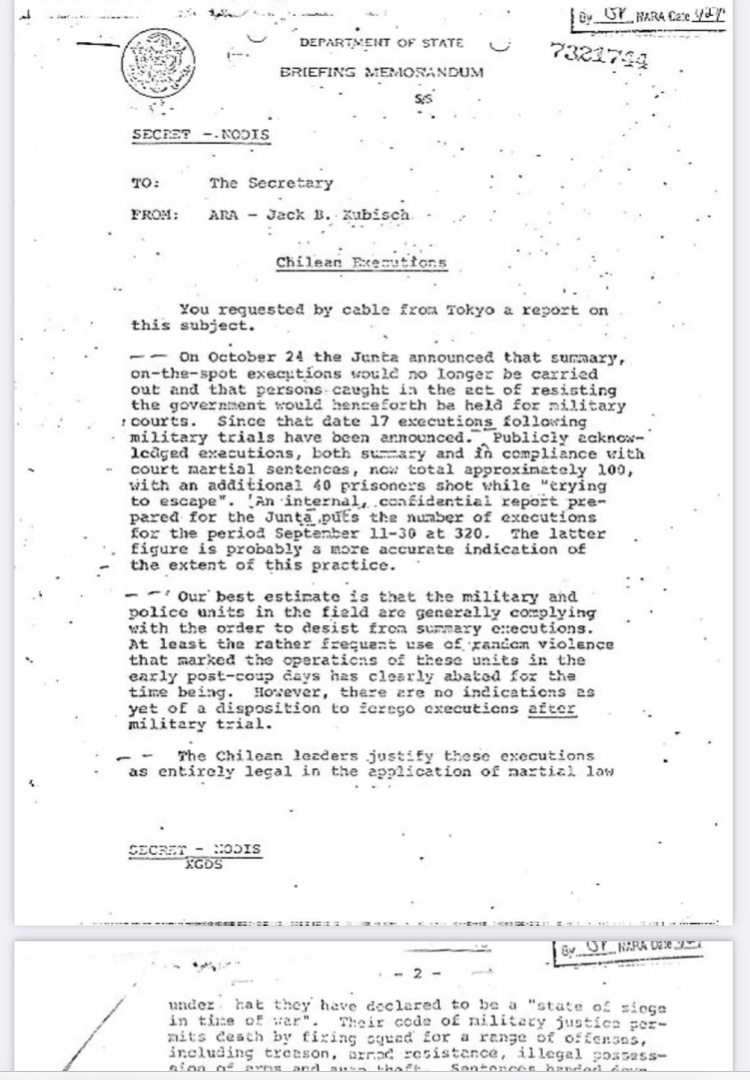

What we didn't know at the time was that the firm we worked for (then still privately owned and with a “Frères & Co.” still appended to its name), had been tangled up in the military coup that Pinochet engineered against Chile's democratically elected President, Salvador Allende. (To be clear: the coup was far more directly enacted with help from the US Central Intelligence Agency and with the enthusiastic support of the Nixon administration's Henry Kissinger. But US corporations like ITT, with links to Silicon Valley, played a role, and that is sadly where Lazard tripped.)

The date of that coup was September 11, 1973. The entanglement that linked Lazard Frères to Pinochet (and thus to the murder of thousands of peaceful civilians whose only "crime" was an adherence to democratic processes) was ITT, on whose board legendary Lazard Frères Director Felix Rohatyn (“The Man Who Saved New York City from Fiscal Ruin!”™️) had served.

ITT had first denied that it had sent any monies in support of the coup. But ITT later admitted that they sent at least $350,000 to Chile for "democratic, anti-communist" purposes. Never mind that Allende had been democratically elected, and wasn't a Communist — Pinochet's military still used ITT's money to murder Allende's supporters. How did they murder them? They threw them out of airplanes, they stabbed them, they shot them, and sometimes they tortured them to death.

And what would encourage ITT to send such a large amount of cash to defeat a democratically elected, non-communist President of Chile? Two issues:

1. Per The New York Times, Allende had nationalized an ITT subsidiary, (which represented a miniscule loss to ITT's overall revenue but apparently still potentially an issue for shareholders); and

2. Per ITT Chairman Harold S. Geneen's own statement at the 1976 ITT shareholder meeting: "...these political contributions were legal under Chile and US law. Moreover, it would appear from the published reports that authorities of the US government both knew of and encouraged at that time funding of this type, by several corporations, as furthering the US Government's own objectives."

In fact, according to a May 13, 1976 New York Times article: "...at a Senate Foreign Relations subcommittee hearing in April 1974, ITT officials acknowledged an offer of 'up to seven figures' made to the office of Secretary of State Henry A. Kissinger and the State Department in support of a 'constructive' United States Government plan concerning Chile."

Up to seven figures in 1970 dollars. But from a risk/benefit standpoint, it was cheap. The neoliberal policies that were put in place after the military coup against Allende made US corporations an obscene amount of money.

In the 21st of 24 paragraphs of the same article, The New York Times notes that "The CIA has acknowledged spending $8 million from 1970 to 1973 in a campaign directed against the leftist Government of Mr. Allende. He died in a military coup in September 1973. ITT officials have categorically denied that it dealt with the CIA."

All of this was very embarrassing for poor Mr. Rohatyn, which is probably why we low-level staff who worked for Lazard never heard about it. (At the time of the 1974 Senate hearing, I was six years old, and some of my coworkers were infants.) I learned of the ITT issue decades later reading William Cohan's excellent book about Lazard, a book which was not well-received by the firm, at least not publicly.

In reviewing Rohatyn’s lengthy New York Times obituary, I note that it was Katherine Graham who then advised him to resign from the ITT board, and that his subsequent "shepherding New York City toward financial stability" (the famed rescue) was in penance for the ITT fiasco. And of course, we had long been instructed not just at Lazard but by the entire media in New York that Rohatyn's rescue of New York City was heroic. And how could it not be? He was friends with Jackie Onassis. Felix was virtually a saint.

It is an indication of what a bubble I lived in that it was not until 2016 that a former New York City public employee informed me of who paid the price when that rescue was delivered.

*****

September 11, 1973 was "Chile's 9/11". And at the time of the 1998 Lazard meeting, our own 9/11 loomed on the horizon.

The morning of September 11, 2001, started predictably enough. I was no longer at Lazard, but at another French banking concern in Manhattan. As I raced out of my Queens apartment to get the N train, it was announced on WNYC that a plane had hit the World Trade Center. On the elevated train, I mentioned to a young Greek neighbor reading the newspaper who was also on her way to work, "hey, they said a plane crashed into the World Trade Center."

And she and I and another young professional, a pretty, olive-skinned girl reading a law review journal, stood up on the elevated train and stared at the World Trade Center Towers that were visible from the window. I think of these women often, not because of 9/11, but because it reminds me that this is who we were in our youth. We were not the cartoonish vamps of "Sex and the City", obsessed with cocktails, men, and fashion; most of us were just working people who led ordinary lives, and who had our own quiet ambitions to do something more.

"That's strange," I said, "it looks like the fire must have jumped. Because there's smoke coming out of both towers." The girl with the law journal started looking at her Blackberry, and her face became increasingly distressed as she read. I didn't think much of it until I reached the office and was informed that there had been multiple strikes, in NYC and at the Pentagon.

At work, everyone was nervously glued to their computer screens. "When can we go home?" my colleagues kept asking. Regardless of whether you were in midtown or downtown, it didn't seem wise to sit around in a towering office building after having watched not one but two office towers crumble to dust. I was told that returning to Queens would be impossible because the bridges and subways had been closed. But when we were allowed to leave work (maybe around noon?), I walked over to the 59th Street Bridge, and saw it was only closed coming into the city; pedestrians were allowed to walk out, and emergency vehicles were allowed to drive in to Manhattan. So I ran/walked (in heels), along with thousands of other people, to Queens.

The only vehicle I remember seeing on the bridge in our direction was a garbage truck; there was a shoeless woman in a business suit clinging to the back of it, as there were few if any cabs out of downtown. Once in Queens, I managed to hail a livery cab and tried to pick up as many people as possible who needed to head north toward Astoria.

"I can't believe a plane hit the Pentagon," someone muttered blankly.

"How can you worry about the Pentagon?" fumed a young man who got into the cab with us, "thousands of people are dead in those towers!"

I was the last to get out of the livery cab at Ditmars. I paid the driver and told him, "Look. Things are going to get bad. I'm worried about what could happen to you if people think you're..."

"I'm Colombian," he said, pointing to his flag decal.

"You think they'll recognize that flag?" I asked him. He didn't disagree.

"Take this," I said, handing him some extra money over the tip, "do me a favor, go buy some American flag decals for your car. Put them all over the back. Make it loud."

I wasn't wrong. For months after 9/11 in our neighborhood, people from Long Island were coming in and beating up our neighbors who weren't even Muslim, let alone "middle eastern". All you needed to be targeted was to have brown skin and dark hair.

Meanwhile, the cable news stations kept announcing how "united" everyone in New York City was. United! It was a virtual mantra. On September 10, the entire country hated New York City, and a lot of people in New York had a healthy disregard for everyone but their neighbors. But now, the media informed us, everyone was united.

"Yeah," cracked my immigrant Albanian neighbor, a basketball player at Hunter College who couldn't be more assimilated into American culture, "New Yorkers are united, all right. United in beating the crap out of us Muslims."

"People in this City have gone out of their minds with hate and fear," a news photographer told me a few days later, as we stood in the smoky air trying to make sense not only of the WTC attacks but of what was happening in response. There were a few military tanks in midtown, which didn't ease the tension. And rampaging "patriots" from Long Island beating on our neighbors were the least of it. The response of our government was predictable: The Bush administration won overwhelming support to bomb and occupy Afghanistan; later Iraq.

My then-boyfriend had joined the Marines to pay for college, and was at risk, along with his reserve squadmates, of being stop-lossed. Under that threat, they re-upped for a pittance. To say that he felt ambivalent about his deployment would be an understatement. But in that moment, especially in New York, to voice any dissent against the US response was to invite more vitriol than you might be ready to handle.

Unlike that long-ago moment at Lazard, this time I managed to speak up, timidly. It wasn't a conscious choice. I felt that I hadn't even been allowed time to mourn the people I knew who were killed in the WTC attacks because almost immediately after 9/11, I had been thrust into the position of having to look out for my immigrant neighbors who were being targeted by "patriots".

At one point I had to ask the kindly head of BNP/Paribas to address the vitriolic comments directed by staff toward our young Lebanese receptionist (who was so bullied after 9/11 that she sobbed uncontrollably through her lunch breaks.)

"Everett, she's not even Muslim, she's Christian, and they won't stop acting like 9/11 is her fault. She's a nervous wreck." He looked at me blankly. I stammered on: "And for God's sake, even if she were Muslim, 99.9999% of Muslims have nothing to do with this."

Everett said tersely: "I have no idea what you're talking about," and he walked away. The nicest boss in the world wouldn't lift a finger for that girl at the reception desk; she had the wrong color skin, and it was apparently the wrong time for almost everyone to do the right thing.

Wealthy, liberal friends I knew who had gone out into the streets to protest the Supreme Court decision Bush v. Gore shifted to a hawkish, neoconservative position. For me, the fantasy of New York was forever changed. No doubt many generations before me had already come to this realization over other, worse injustices; I barely even knew where Riker's Island was located at that time.

Heartbroken and exhausted, I left the city in 2002, and went to the Hudson Valley for a year. It was the era when the Bush administration was seeking to invade Iraq. There was an older hippie couple that would sometimes stop by the Civil War-era brick farmhouse where I was renting. They were convinced (rightly) that any invasion of Iraq would be a disaster, but the scope of what they described was over my head. Sometimes, they would ask me about my boyfriend's deployment, concerned. They were kind people, I think about them often.

After another deployment, my boyfriend returned. It was 2003, the year we dropped between 1,000 to 2,000 tons of depleted uranium on Iraqi civilians. "I was looking down at this place from the plane," he told me one night before he fell asleep, "and I just thought they should bomb all these people, we would all be better off." I knew he didn't mean that, that he only said it in anger, but it frightened me that he might mean it, that the deployment had changed him. He had never expressed anything like that before.

In fact, the war had changed the entire country, it had made us all more callous and stupid. But 22 years after we bombed civilians in Afghanistan in response to the destruction of the World Trade Center, and 20 years after we permanently destroyed the infrastructure in Iraq, setting off a cascade of disasters across the middle east, we are no closer to coming to grips with our foreign policy.

Last week, Ariel Dorfman, a survivor of Pinochet's violence by dint of exile, wrote an article in The New York Review of Books about this 50th anniversary of 9/11. As I once said to the Colombian livery cab driver 22 years ago, "do yourself a favor and...." But this time I'm not begging you to try to buy a bunch of US flag decals to look more "American" to protect yourself from attack. I'm suggesting instead that you read every word of Dorfman's article.

©️Eva Chrysanthe, 2023